On Sept. 2, 1933, Michigan’s first parimutuel horse race was run at the State Fairgrounds in Detroit.

Ninety years on from that inaugural wagering pool, the ups and downs of Michigan’s horse racing industry have mirrored those of the Motor City itself. About a dozen tracks have come and gone, with only Northville Downs, a harness racecourse in suburban Detroit, remaining.

Opened in 1944 by the Carlo family, Northville was the first Michigan track to offer “sustained parimutuel betting,” according to the Detroit Free Press. As they prep for the 2023 meet’s opening night on Friday, Northville’s horsemen will do so with the knowledge that the track’s 80th year at the existing venue will be its last, as it’s been slated for redevelopment since a sale agreement with a housing company was announced in 2018.

If a relatively young, gleaming racetrack like Chicago’s Arlington Park can be assigned a date with a bulldozer, then it’s hardly surprising to see a run-down track like Northville destined for the same fate. But unlike with Arlington, whose demise can be pinned solely on Churchill Downs Inc.’s craven self-interest, Northville’s operations manager, Mike Carlo, and his brother, John, are close to making good on their promise to build a new racing facility a few miles down the road in Plymouth Township, on land that was once occupied by the Detroit House of Corrections’ prison farm.

“The Carlo brothers have acquired a 125-acre parcel,” said Tom Barrett, president of the Michigan Harness Horsemen’s Association. “They’ve gone through the Board of Trustees and two hearings with the city on this project. My understanding is they’re going to the April board meeting for final site approval.”

‘They like racing up here’

Harness — or standardbred — racing and thoroughbred racing are two different animals, literally and financially. Whereas the larger thoroughbreds must be stabled at an actual racetrack while they’re actively racing, standardbreds can be shipped in and out with relative ease.

“Hazel Park (which closed in 2019 after hosting both thoroughbred and standardbred racing) said it was four times more expensive to conduct thoroughbred racing than harness racing,” said Barrett, pointing to such costs as on-track stabling, security, and track maintenance. “With this new facility, by midnight there won’t be a horse on the ground. You ship in, race, and go home. Thoroughbreds can’t do that. They have to be on the grounds. If you make your money with simulcasting, then harness is a much less expensive way to conduct live racing.”

Then there’s the fact that people who’ve spent their entire life in the sport, as Chucky Taylor and Art McIlmurray have, are still considered capable of both training and driving (standardbred parlance for “riding”) their horses well into their golden years (both Taylor and McIlmurray are 64), eliminating the need to cut lilliputian jockeys in on the action.

“It’s very exciting to have something like a new track built,” said McIlmurray, whose late father, Wally Sr., was harness racing royalty. “My dad had eight brothers, and all eight brothers drove and trained horses. I’ve been doing it my whole life. I was brought up around this. I’ve been at Northville Downs ever since I was born. When we were kids, that was our life.”

The same goes for Taylor, who got his parimutuel license at Northville at the age of 18.

“I started probably when I was 12 or 13 going out to the fairgrounds at Kalamazoo,” he said. “My father got started with it toward the time he was getting ready to retire. He bought a cheap horse and one thing led to another. Then he bought a little piece of farmland out in Comstock and we just kind of went from there. I started kind of going with people to the races, and next thing you know, I was involved.”

Guys like McIlmurray and Taylor used to be able to spend most of their time in Michigan, but not anymore.

“At one time, we were one of the biggest states in the country. We had half a dozen tracks. We were racing every day all year long,” said Taylor. “I raced in Ohio all winter — Miami Valley, Northfield Park. I have to if I want to do this for a living.

“It’s devastating what’s happened, really. A lot of the younger guys have moved to New Jersey, Indiana. They had to move to keep going. At my point in my life, I don’t want to move and start over someplace. I don’t know how much longer I’m gonna do this. It depends on this [new track].”

When talking about the advantages a state like Ohio’s horse racing industry has over Michigan’s, Taylor singled out “the racinos — casinos right at the racetrack.”

Still, he thinks once the new Northville Downs opens (racing at the current facility is scheduled to proceed through the 2024 meet), Michigan horse racing will be back on an upward trajectory.

“If we get a nice, new facility, people will come back. Some Friday nights when the weather’s nice, we have quite a crowd at Northville. They like racing up here, they really do.”

Hungry for more revenue streams

Barrett, the state harness association’s head honcho, also grew up in the sport.

“I started when I was a kid,” said Barrett, a commercial banker who jokes that that’s his second job. “Right now, my son and I have a stable of five at what was formerly Perfecta Farms. We have 60-head here and a group of horsemen getting ready to run at Northville and some getting ready to run colts at the fairs.”

In talking about Michigan’s horse racing heritage, Barrett feels it’s “certainly undervalued” and expands upon Taylor’s thoughts about what’s holding the state’s industry back.

“If you look at what surrounding states have done, the most parallel example would be Ohio. Prior to VLTs (video lottery terminals), they were probably worse off than we are now. They were down to 50 foals a year, purses were down. The governor needed a new revenue source and some money quick, so he instituted VLTs there, they got millions per track as a licensing fee, and I think Ohio will have 2,500 to 3,000 foals this year.

“Their breeding industry has exploded and the general rule of thumb is every foal born, when it reaches racing age at 2, has generated $35,000 in economic activity — feed, fees, hay and grain. It’s a great economic multiplier. When you go from 50 foals to 2,000 or 2,500 foals, you’re talking about a significant amount of money.”

Barrett also pointed to Indiana, with its racinos, and the Canadian province of Ontario, with its slot machines, as examples of neighboring jurisdictions where the horse racing industry is handsomely subsidized. Given that Michigan is one of the few states with sports betting and casino gaming in both retail and mobile formats, it’s somewhat surprising to hear that the horsemen are still struggling to keep the lights on.

“We get a share of the revenue tax from sports wagering and iGaming,” Barrett explained. “We get a small piece of that capped at $3 million a year. Given the tools that the casinos have been given, we think raising or eliminating that cap is more than reasonable. The second thing we’re looking at is HHR (historical horse racing), and the third piece is, potentially, slots.”

To get a racino at Northville, Barrett said, “The biggest hurdle would be Prop 1 and the casinos, who have a monopoly on slot machines in Michigan. There wasn’t any local or statewide referendum on iGaming or sports wagering. The underlying premise of the three Detroit casinos was you had to drive to Detroit and wager at their facility. But now a kid can turn his phone on and lose his paycheck on BetMGM.com without ever having visited Detroit.”

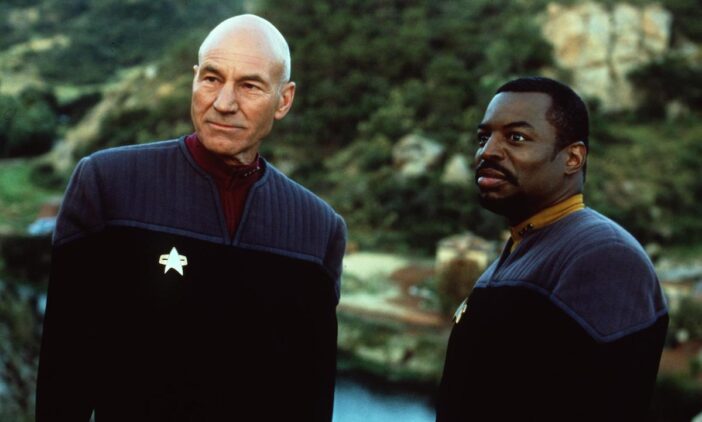

Photo: HUM Images/Universal Images Group via Getty Images